Feral swine are a threat to Texas agriculture, public lands and wildlife. What’s stopping them?

April 17, 2023

BY: LAUREL MILLER

If you’re new to Texas, you might not be aware that the state is waging a war against a formidable, four-legged foe, and the state’s farmers and ranchers are on the front lines. Any native, however, can tell you that feral hogs are so ubiquitous, they’ve become part of the popular culture, inspiring jokes, video games, t-shirts- even businesses (Wild Boar Man Soap).

While feral hogs have been documented in at least 35 states, Texas has the highest population of these voracious invaders, with an estimated three million animals roaming wild on private and public lands. These swine are ancestors of the first domestic pigs, which arrived in Florida in the 1500s with Hernan De Soto, and Eurasian wild boars, which were imported for hunting purposes in the 1930s.

These animals have for generations bred with one another, as well as escaped livestock. The term feral, then, applies to both pigs that have been breeding in the wild for generations, or recent escapees, which quickly adopt wild characteristics, both behaviorally and physiologically.

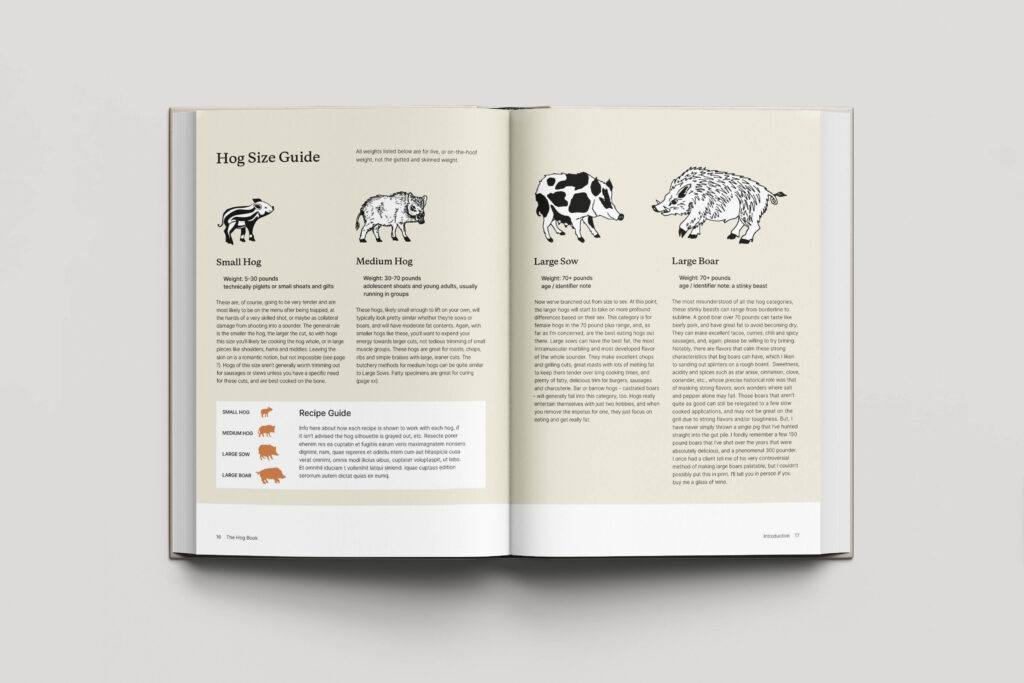

Feral hogs are classic opportunistic omnivores, but they’re also equipped with sharp tusks, tough hides, few natural predators, and a gestation period of just under four months. Sows can breed as young as six months and have one to two litters a year of six to ten piglets. The hogs live in family groups known as sounders and are primarily nocturnal. Like domestic pigs, feral swine engage in rooting behavior, digging up the soil with their snouts in search of food.

As a result, wild pigs destroy the root systems of natural and cultivated grasses including crops, forestry and public park plantings, causing over 180 million dollars a year in damages to private agricultural land, alone. These wily creatures also consume the eggs of native birds like quail and wild turkey as well as those of sea turtles, and feed on the young of deer, sheep, goats and cattle. They destabilize wetlands, muddy waterways (which kills fish and other aquatic species) and compete with native species and livestock for food.

Cattle ranchers like Matthew Ashcraft of Matagorda’s Ashcraft Cattle are engaged in an ongoing battle to simply manage hog populations on their land. “Over the past decade, they’ve gotten out of control for us,” he says. “Where they root up and kill the grass, invasive weeds and brush take its place and that negatively impacts the land’s value for agriculture production and harms our equipment.” Ashcraft adds that to ensure planted ground can take root, it’s necessary to check the fields every two hours, around the clock.

Even high-density urban areas like Austin aren’t safe from hog encroachment. Jesse Griffiths, chef-owner Austin’s Dai Due restaurant and butcher shop and the New School of Traditional Cookery says there are thousands of pigs causing damage along rivers, around Lake Travis, and congregating on areas like playing fields.

“Feral swine are a formidable foe and a scourge to every ecosystem and agricultural product in Texas,” says Dr. John Tomeček, an associate professor and extension wildlife specialist and Texas A & M who specializes in feral hog management. “Another very real concern are novel and zoonotic (transmissible animal-to-human) diseases as a threat to human health and the domestic pork industry.”

Tomeček says he’s always been interested in managing conflict and ecological damage between humans and wildlife. His work at present focuses on researching new methods of control and assessing environmental impact. As co-chair of the Texas Wild Pig Task Force and chair of the National Wild Pig Task Force, he also does hog control.

In Texas, feral hogs legally belong to the landowner on whose property they stand, says Tomeček. “There are a number of opportunities for support from government agencies, both in terms of education to do one’s own control as well as direct control, which is having someone come do it for you.”

Adds Ashcraft, “For ranchers and farmers with vast amounts of land, aerial shooting is by far the most effective way to slow population growth. The damage from feral hogs costs Texas farmers and ranchers millions of dollars a year.” His brother, Ryan, is a helicopter pilot and owner of Ashcraft Aviation; he assists with aerial direct control for most of the farmers in Matagorda, Brazoria, Jackson, Wharton and Fort Bend Counties.

Integrated pest management (IPM) is the only way to control feral hog populations and eradicating the entire sounder is paramount, which is why corral-style traps are the most effective means of capturing groups of pigs. Toxicants are a controversial method of hog control, due to their ability to affect or kill non-target species including carrion eaters, although Tomeček says two new products, produced by private companies and funded in collaboration with the state of Texas and USDA, are currently undergoing trials.

If you can’t beat ‘em, eat ‘em

For Griffiths, feral hogs are a pestilence with one advantage: Their meat is exceptionally flavorful, due to their diet of foraged acorns, pecans, and grasses. Since 2007, he’s been on a mission to educate diners and the general public about feral hogs through a culinary lens- an extension of his longtime commitment to supporting Texas family farms, ranches and Gulf seafood (all of Dai Due’s fresh product comes from Texas, as do half most of the dry goods).

It should be noted that to serve or sell feral hogs for public consumption, the meat must be inspected by the USDA. Dai Due purchases Hill Country-harvested, state-inspected whole carcasses from Dutchman’s Market in Fredericksburg.

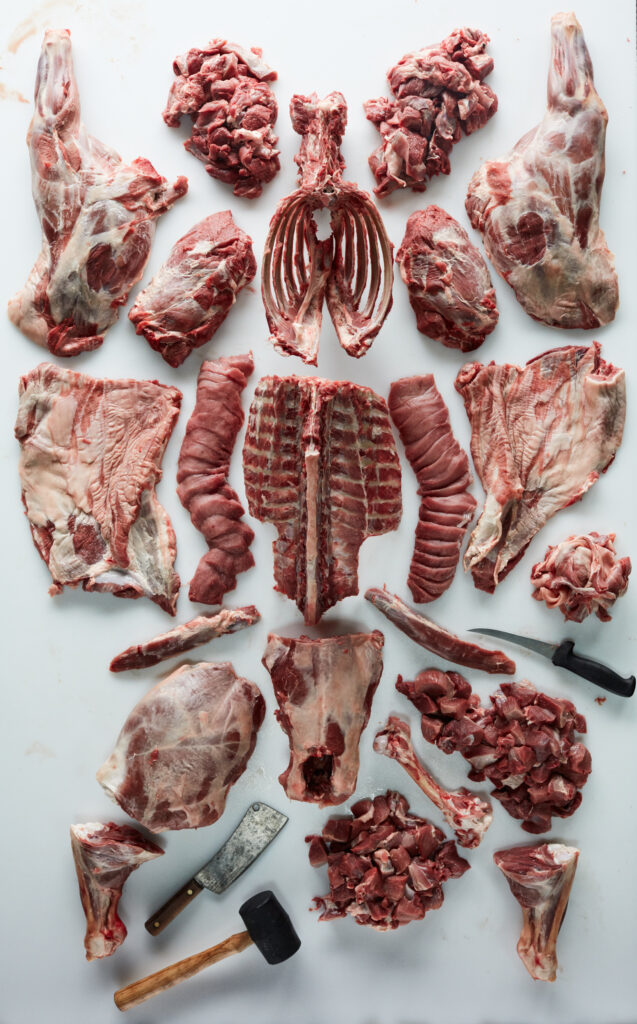

In addition to authoring a well-regarded work called The Hog Book that details hunting, trapping, butchering and cooking feral pigs, Griffiths serves the meat at Dai Due and transforms it into charcuterie at the attached butcher shop. There are even lard-based apothecary goods like beard and lip balms made by Ingram’s aforementioned Wild Boar Man Soap. For his cookery school, he holds workshops and multi-day hunting trips that include field dressing, butchering and cooking the resident feral hogs and other game.

“I see my role, with regard to this issue, as educating people about the culinary side, but it’s also about promoting responsible use of our wild resources and empowering our community to utilize local foods to their fullest,”

Jesse Griffiths, Austin’s Dai Due

“I see my role, with regard to this issue, as educating people about the culinary side, but it’s also about promoting responsible use of our wild resources and empowering our community to utilize local foods to their fullest,” says Griffiths. “A lot of hunters also don’t know how to go about breaking down a hog and after years of requests, I started teaching classes and wrote a book to address these, and other questions.”

Off the clock, Griffiths hunts only to obtain food for personal use. “I see hunting as part of my grocery list, and I only take what I need,” he says. He touts hog meat as being “leaner and more flavorful than domestic pork. There’s a myth that the meat is rank, but a 200-pound pig that’s been feasting on acorns is the best pork you’ve ever tasted.” Because the fat content varies depending upon genetics, season and gender, the rule of thumb is to cook cuts like chops, loin, and tenderloin quickly. Bone-in cuts, stew meat and shoulder meat need time to break down, so they require low, slow cooking.

While feral hog eradication remains elusive and control methods are fraught with red tape and dissention amongst various factions, conservation remains a common goal. “Feral hog management should be primarily the responsibility of the landowner,” says Ashcraft. “What the state and federal level could do focus on wildlife refuges and public lands that serve as breeding grounds for feral swine. “It may be a refuge, but it’s about helping native species instead of letting hogs root them out of their habitat.”

Tomeček agrees. “I know that (we) make a positive difference for wildlife and the environment, with every hog that’s removed.”

Seasonal Fishing on the Texas Coast: When, Where & Who to Go With

November 17, 2025

Texas Tall Tales: Spooky Folklore and Legends That Still Haunt Us

October 14, 2025

Rice Farming: The Heartbeat of the Texas Coast

September 30, 2025

Fried Dove Breast Filets with Cream Gravy and Angel Biscuits

September 11, 2025

Hearty Venison Chili Recipe

September 11, 2025